Today I was about to step out into the rain when I heard a song coming from someo

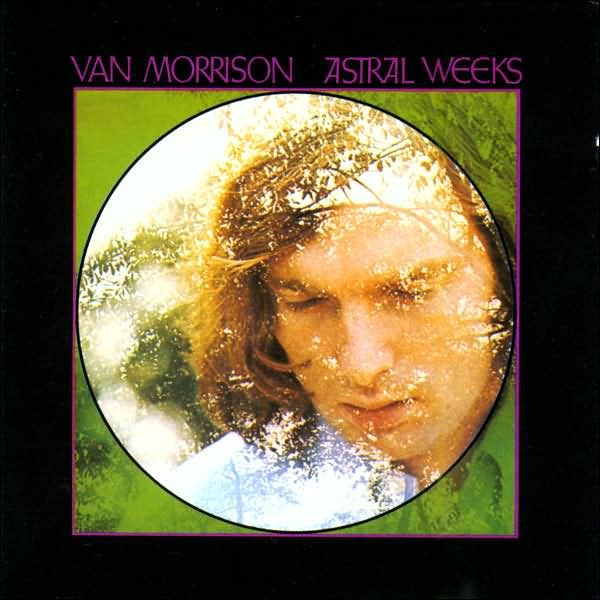

ne's apartment: "...now here comes the man--and he says the show must go on..." a song I liked very much but hadn't heard for awhile. It was "Ballerina" by Van Morrison, from the album Astral Weeks, which to me always sounds like a lush, green spring. Maybe it's the album cover...

ne's apartment: "...now here comes the man--and he says the show must go on..." a song I liked very much but hadn't heard for awhile. It was "Ballerina" by Van Morrison, from the album Astral Weeks, which to me always sounds like a lush, green spring. Maybe it's the album cover...I never thought about it before, but Van Morrison is a writer who often brings a lot of divergent ideas into one song. Somehow he's able to put an unexpected collection of people and places together and connect them all to a certain setting and mood. For those of you who haven't listened to much of his music, try to forget "Moondance" and oldies stations

for a moment and consider a song like "Will You Meet Me in the Country in the Summertime in England," where he talks about W.B. Yeats, T.S. Eliot and William Blake smoking dope, Mahalia Jackson (a gospel singer), Jesus, Avalon (mythic resting place of King Arthur), and the Church of St. John (someplace in England?), and they're all there, in the country in the summertime in England. Or there's "St. Dominic's Preview," where he

for a moment and consider a song like "Will You Meet Me in the Country in the Summertime in England," where he talks about W.B. Yeats, T.S. Eliot and William Blake smoking dope, Mahalia Jackson (a gospel singer), Jesus, Avalon (mythic resting place of King Arthur), and the Church of St. John (someplace in England?), and they're all there, in the country in the summertime in England. Or there's "St. Dominic's Preview," where he mentions Edith Piaf's soul, Belfast, Buffalo, San Francisco, and the Notre Dame cathedral.

mentions Edith Piaf's soul, Belfast, Buffalo, San Francisco, and the Notre Dame cathedral.Van Morrison (born George Ivan Morrison) also brings together two musical divergences with his name: Jim Morrison, the singer for The Doors, and Van Cliburn, a famous classical pianist. Most people today know Jim Morrison, but few know Van Cliburn, though at one point his was a household name. In 1958 he won the first International Tchaikovsky Piano Competition, put on by the Soviet Union to demonstrate Soviet superiority. Apparently, the contest's judges had to ask Premier Kruschev for permission to give the prize to an American, and Time magazine called Cliburn "The Texan who conquered Russian." His full name is Harvey Lavan Cliburn.

The Spanish word bodegon means pantry, but is also used to refer to still-life paintings (this at least I know). This is because in the Spanish tradition still-lifes often depict objects from the pantry. Like for instance a coffee cup.

The Spanish word bodegon means pantry, but is also used to refer to still-life paintings (this at least I know). This is because in the Spanish tradition still-lifes often depict objects from the pantry. Like for instance a coffee cup.